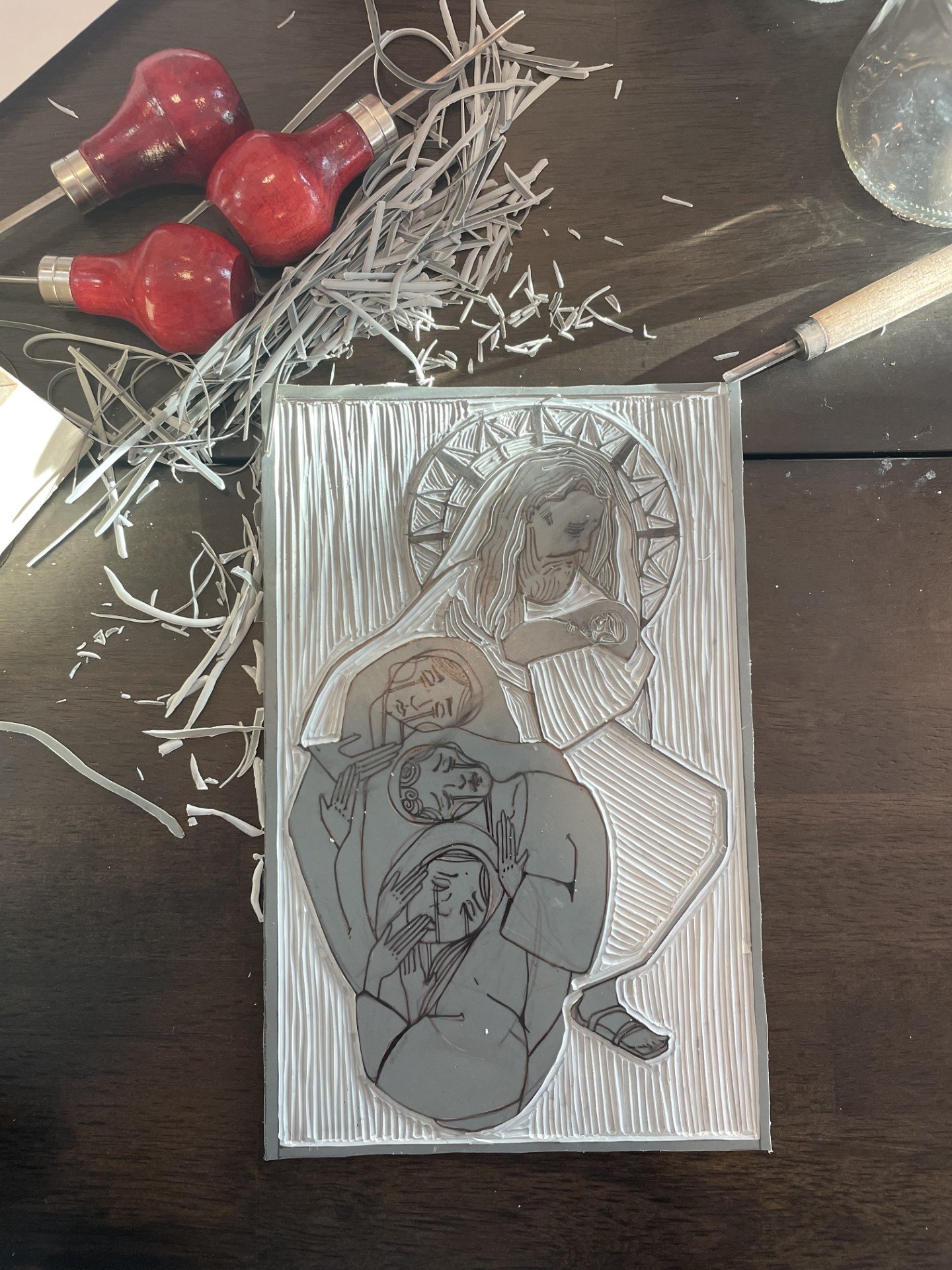

I’ve always thought one of the most upsetting lines in Scripture is God’s chilling assessment of human beings just prior to flooding the earth: “I am sorry that I have made them” (Gen 6:7). Of course, these words are only half as chilling as the floodwaters themselves, which cover the earth and destroy all living things.

Was God really sorry for making people? No, I don’t think so. Like the flood itself, God’s words express a deeper meaning, a sorrow so profound that it is expressed here in a plaintive hyperbole, a purposely shocking lament. The broken heart of God is groaning! Yet it is not God we humans harmed but one another. According to Genesis it was the inclination of the human heart that grieved God’s own heart (6:5-6). It was the way we treated each other.

At the end of this dark story of divine disappointment and devastating destruction, a covenant is established, the first in the Bible. It is a covenant made not only with humans but with animals, with all of creation. This is a covenant of peace. All that humans are asked to do is to not kill each other (9:6).

There are many ways to kill: in thought, in word, and in actual deed. As these days pass in our nation and our world, it seems almost impossible that we could ever get along, that we could treat each other in a way that will not grieve the heart of God, or that we could stop killing one another in thought, word, and deed. God has promised to never flood the earth again, but we can still drown ourselves.

We know the only antidote is love—the one gift that always builds up and never tears down—the one spiritual gift that can’t be lorded over someone else or twisted for power or self-promotion, the one that is never rude, that rejoices in the truth: the one that never ends (1 Cor 12–13).

Martin Luther King, Jr., whose life we celebrate this week, said many things that this nation treasures, and among those: Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that. Only love stops the destruction of the other—mentally, verbally, physically, socially. Only love as deep as our divisions can stop this flood of our own undoing.

* * * * * * * * *

A version of this reflection was originally published here, January 2021.